Artificial intelligence (AI) used to exist only in the imaginations of science fiction writers – the self-preserving HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a conquering Skynet in The Terminator and an affectionate Samantha in Her. Now AI is here, recommending the next binge-worthy flick, answering voice requests about almost any topic, defeating chess Grandmasters… self-driving vehicles, computer-generated art and medical diagnoses1 will soon feel just as familiar.

Alongside this technological evolution, preventable diseases are also on the rise. Diabetes is estimated to double in the next 20 years2, while district health board financial reports from April 2021 show Aotearoa’s entire health sector is more than half a billion dollars in debt. The script is written: AI will begin to take a leading role. The question is whether AI is the potential saviour or an unwitting villain in the saga of overburdened healthcare.

Why the deep dive into deep learning?

Over 250,000 Kiwis have diabetes and a quarter of those have some form of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Requiring retinal images at least biennially, the demand for grading is growing and hard-working diabetic screening services are already at capacity.

Introducing deep learning could help dramatically with this pressing issue. Traditionally, computers solve problems by taking inputs, applying human-programmed rules and creating valuable outputs. Simple, if the inputs are as trivial as frame details and pupillary distances to output minimum blank size; very difficult if the inputs are complex retinal images for DR grading.

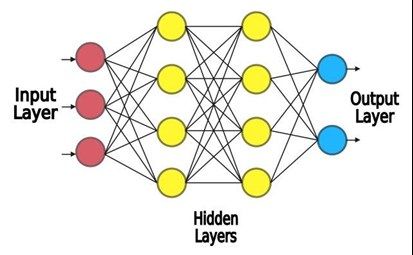

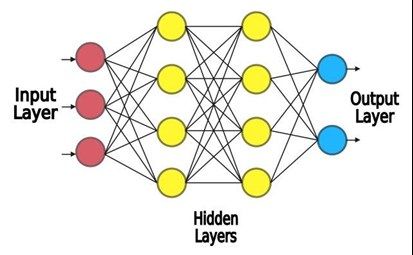

When looking at an image, an overwhelming number of subconscious processes take place in the human brain. Therefore, for a computer, the traditional, rules-based programming approach is not practical. Instead, machines are programmed to learn from data – machine learning. Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, is inspired by the brain’s architecture. Multiple layers of virtual neurons interconnect and interact, creating an artificial neural network (Fig 1).

Fig 1. A simplified view of an artificial neural network

Fig 1. A simplified view of an artificial neural network

A good neural network for processing images is the convolutional neural network (CNN). The CNN closely resembles the inner workings of Hubel and Wiesel’s biological visual cortex3. Retinal images are translated from pixels into a numbered array and fed into an input layer of the neural network, similar to the eye’s photoreceptors. The input layer connects to hidden intermediate layers of neurons, akin to the ganglion cell receptor fields. The earlier hidden layers respond to horizontal or vertical edges, like an edge of a haemorrhage or a blood vessel. The outputs of these then act as inputs for later hidden layers. These neurons respond specifically to a haemorrhage and not a blood vessel, while other neurons respond to a blood vessel and not a haemorrhage. The artificial neurons respond in this way because they intelligently learn from previously graded retinal images. The responses are combined to give an overall output: the DR grading.

In the same way eyecare professionals use mental shortcuts to quickly grade numerous retinal images from diabetic screenings, a good AI system uses deep learning to do the same, making them as effective as the top minds in the field4, while having limited human input, being camera agnostic and location independent. But grading DR is just one example of AI’s medical application abilities.

With great power comes great responsibility

Ting et al (2017) found most AI models can grade retinal images to the same level and even outrank the best retinal graders4. The advantage is that an AI doesn’t get fatigued, stressed, or have a bad day. “(AI) is an evolution of statistics that’s been used for decades,” says Dr Phil Turnbull, University of Auckland senior lecturer and registered optometrist. “Deep learning is the newest addition, made more powerful with modern clustered computing.”

Health, however, is a conservative business, says Dr David Squirrell, ophthalmology lead of the Auckland Diabetic Screening Service and chief medical officer at Kiwi AI screening development spin-off firm Toku Eyes. When introducing any new technology, there is always the risk of unintentionally causing harm, he says.

Another problematic issue when delivering an AI product is that Indigenous people and minority groups are vulnerable due to existing bias in health data. Data used to train the AI must resemble the population it will be used on. For example, purely Caucasian data would be inappropriate to train an AI model used on the New Zealand population. If the AI has not seen Māori, Pacific Islander and Asian fundi, it may provide unreliable grading for these ethnicities, furthering health disparity.

Moreover, the inner workings of an AI model involves hundreds of neural layers. This means how an AI determines a DR grade is challenging to understand. For instance, say the AI mistakenly develops a phantom correlation where a Pacific Islander’s fundus is graded at a higher level of DR. The AI could then amplify the bias present in real-world data, where an increased proportion of Pacific Island people have DR5. The AI may be mistaking fundus pigmentation for actual DR clinical signs6. Addressing this ‘black box’ issue is still an area of ongoing research. One method currently being investigated uses attention maps to highlight clinical signs while discounting irrelevant background data, showing the AI’s thought process, so to speak.

Security and privacy are also concerns. In 2017, Google’s DeepMind was fined for improper handling of 1.6 million National Health Service patient records in the UK. Closer to home, malicious, non-consented data use would violate Māori data sovereignty, for instance, as unethical practice marginalises Indigenous people and minority groups. So data initially used for good – for training AI – could instead end up aiding insurance companies with their funding models!

A brave new world

If AI performs better than human experts, there is also concern practitioners will be replaced by machines. In his book Deep Medicine, Eric Topol quells this worrying notion, saying that AI will restore ‘the human touch’. With the diagnostic load handed over to AI, the practitioner is actually better able to build a compassionate connection with the patient, he says.

Professor Steven Dakin, head of the School of Optometry and Vision Science at Auckland University, envisions deep learning will expand the scope of optometry. Despite providing the best level of care, public sector ophthalmologists are a resource stretched thin; AI can help fill this gap, assisting optometrists with their diagnoses, he says.

AI applications go beyond DR. The eye is the only organ that allows assessment of an individual’s microvasculature and central nervous system without invasive techniques. Oculomics involves AI assessment of retinal imaging for systemic ailments such as cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease7. AI can also detect keratoconus from coloured corneal maps8. And AI doesn’t have to be purely medical – AI-assisted booking systems and clinical notes can also ease the administrative demand in eyecare.

Conclusion

Is the future HAL 9000 locking professionals out of work, Skynet taking over the eyecare industry, or patients developing intimate relationships with Samantha? From fiction to fact, AI is already impacting society and now it is on the cusp of providing a response to the growing demands of eye- and healthcare. It can outperform human expert DR graders and is immune to fatigue and stress. It is a powerful tool, neither good nor bad. The morality stems from the wielder. Used for profit and greed, AI will likely become villainous, but applied with an ethical lens, and built with ethnic collaboration, AI could, and is likely to, become a hero in our healthcare story, allowing optometrists and ophthalmologists to build even stronger connections with their patients and the wider eyecare community.

References

Meskó B, Görög M. A short guide for medical professionals in the era of artificial intelligence. npj Digital Medicine. 2020;3(1).

PwC. The Economic and Social Cost of Type 2 Diabetes. ; 2021. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://healthierlives.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/Economic-and-Social-Cost-of-Type-2-Diabetes-FINAL-REPORT.pdf

Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. The Journal of physiology. 1968;195(1):215-243.

Ting DSW, Pasquale LR, Peng L, et al. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;103(2):167-175.

Ramke J, Jordan V, Vincent AL, Harwood M, Murphy R, Ameratunga S. Diabetic eye disease and screening attendance by ethnicity in New Zealand: A systematic review. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2019;47(7):937-947.

Araújo T, Aresta G, Mendonça L, et al. DR|GRADUATE: Uncertainty-aware deep learning-based diabetic retinopathy grading in eye fundus images. Medical Image Analysis. 2020;63:101715.

Wagner SK, Fu DJ, Faes L, et al. Insights into Systemic Disease through Retinal Imaging-Based Oculomics. Translational Vision Science & Technology. 2020;9(2):6-6.

Chen X, Zhao J, Iselin KC, et al. Keratoconus detection of changes using deep learning of colour-coded maps. BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 2021;6(1):e000824.